Italian Renaissance Art Volume One Second Edition Vol 1 Second Edition

I. Studies in the History of the Renaissance

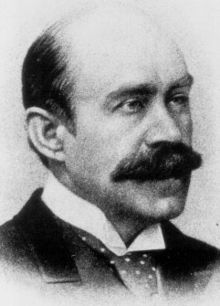

Figure 1: Photograph of Walter Pater

Walter Pater (Fig. one) is known as the main theorist of the Aesthetic movement. His essays laid out the serious and destructive ideas underpinning an art movement whose rebellion was enacted through an embrace of beauty and strangeness. Art historians today are non in the business of proposing to united states of america controversial new ways of living and thinking; yet that is what happened in 1873, when Pater published his collection titled Studies in the History of the Renaissance. He used the art-historical essay as a platform to draw indirectly a lifestyle freed from Victorian conventionalities, particularly those surrounding the human being body. While many authors earlier Pater had used fine art history to meditate more broadly on mod values—well-nigh influentially, the fine art critic John Ruskin, promoting the moral worth of Gothic architecture—Pater puts his own unique spin on the practice. Though Pater has often been alloyed into an plainly normative grouping of Victorian essay writers that includes Ruskin and Matthew Arnold, this piece will highlight some of his more rebellious tendencies, describing how he critiques and even ironizes the scholarly tradition to which he contributes. His double vision is at once serious and transgressive, using the canon of Renaissance art to offering his own idiosyncratic impressions and to implicitly defend the right of others to experience a similar liberty.

In the 1860s, the Italian Renaissance was emerging equally a new subject field for Victorian criticism. Cultured Britons since the eighteenth century had been embarking on "Chiliad Tours" of continental Europe, in which Italy was a prime number destination. Pater himself toured Italy in 1865 with his close friend Charles Lancelot Shadwell, taking in the fine art treasures of Florence, Pisa, and Ravenna. Britain'south

National Gallery and

S Kensington Museum had made a series of high-profile purchases in the 1850s and early on 1860s that reinforced the status of High Renaissance art every bit central to the Victorian catechism.[i] Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian culture was seen to embody many qualities that Victorian thinkers wanted to appropriate, with its flourishing of classical scholarship, its visual artistry, and its prizing of individualism captured in the bold type of the "genius" inventor or artist. Arnold Hauser argues that the Italian Renaissance is itself a nineteenth-century invention, a fantasy of origins for the "individualistic-liberal" embracing a "sensualistic" and nature-based vision more true to nineteenth-century psychology than to any bodily Renaissance history (2). While fully evaluating Hauser's claim is beyond the telescopic of this essay, his insight is valuable for describing the way that nineteenth-century European thinkers used the Renaissance to advance their own mod-solar day concerns. In Britain, some late-Victorian writers promoted a cultural nationalism that alloyed the perceived superiority of Renaissance Italian culture into the economic and political dominance of modern-day United kingdom, thus forging an imaginative link between 2 very different histories and cultures.[2]

Across these more normative uses of the Renaissance, yet, the Italian by also offered a convenient screen by which Victorian authors could explore at a remove disquieting or taboo themes—as in Robert Browning'due south poetic monologues, featuring Italian speakers who were debauched, insane, or even murderous. Italian subjects might adjust to the blazon of the Cosmic, the Southern, the warm-blooded, and the emotional, as opposed to the ostensibly cold-blooded, logical, and morally correct peoples of the North. This stereotyping immune Victorians to accost indirectly some of the more irrational or lecherous strains implicit in their own civilisation.

Pater's essays accept up a ii-sided idea of the Renaissance, both normative and destructive, celebrating canonical artist-heroes even while depicting them engaged in behavior that would take scandalized Victorian society. (For example, many of the male artists he studies, such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, are romantically involved with other men.) His recurring strategy is to appoint with a well-known writer or artist in a mode that seems to hold with conventional wisdom, pretending to fit in with accustomed judgments while at the aforementioned time proposing his own adventurous opinions. Most famously, he quotes Matthew Arnold approvingly in his preface to The Renaissance, merely to overturn Arnold's thought in the following clause:

"To come across the object as in itself information technology really is," has been justly said to be the aim of all true criticism whatever; and in artful criticism the showtime step towards seeing ane's object as it really is, is to know one's ain impression every bit information technology actually is, to discriminate information technology, to realise it distinctly. . . . What is this song or flick, this engaging personality presented in life or in a volume, to me? (iii)[iii]

While Matthew Arnold—Oxford'south Professor of Poetry and representative of the cultural institution—demands that critics put aside personal prejudices to take an objective view, Pater instead promotes the subjective view, focusing on the impression felt by the individual spectator. Arnold'due south dictum implies that a single, objective Truth—"the object"—can be ascertained through a kind of unifying positivist vision. Pater, by contrast, moves to "one'due south object"—the object as it is possessed by a lone viewer, who makes idiosyncratic associations based on his own experiences. Pater implies that the Truth must be replaced by innumerable, diverse, myriad truths.

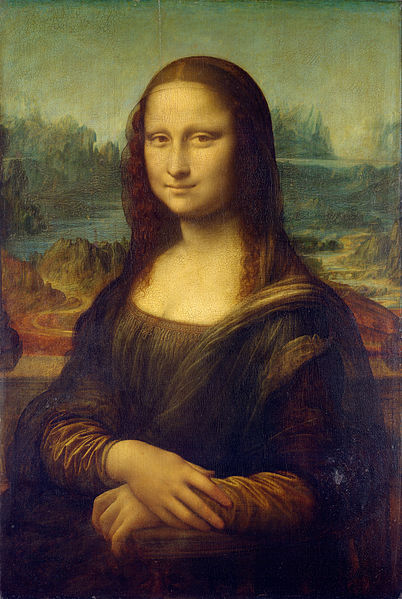

Effigy 2: Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda (Louvre Museum)

Hence the fantasia of The Renaissance, which combines familiar legends and stories of well-known artists with unusual and fifty-fifty startling comments on their artworks. Pater rehearses the customary Victorian visions of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo as genius artist-heroes who create masterpieces rendered in unique styles. Just he also gives u.s., famously, the comparing of Leonardo's Mona Lisa (Fig. 2) to a vampire, seeing in her figure "the lust of Greece, the lust of

Rome" (seventy). He dwells on the more grotesque, discomfiting aspects of Leonardo's oeuvre, from a painting of Medusa's monstrous severed caput to drawings of "clairvoyant" women whom Pater labels "Daughters of Herodias" (65). (Run into Fig. 3.) These are truths for Pater's version of aesthetic experience, a beauty mixed with darkness and death. Jeffrey Wallen notes that the recurring shadowy figures of Pater's essays—the vampire, the specter, the clairvoyant, the god in exile—"all radically confuse the boundaries betwixt historical eras, and between what is living and what has passed on" (1043). These diabolical figures not only serve every bit vehicles for a perverse aesthetics but also embody a theory of historicism, showing how culture's present is infinitely permeable and infiltrated by its past.

Effigy 3: The Caput of Medusa, ca. 1600, formerly attributed to Leonardo da Vinci (Uffizi Gallery)

Pater's challenge to accepted norms of scholarship is most apparent in his ever-shifting and porous account of "the Renaissance" itself. The book opens with a report of ii French medieval tales and concludes with a lengthy essay on the eighteenth-century German language fine art critic, J. J. Winckelmann—thus delineating the Renaissance equally a historical motility that spans six centuries and at least three dissimilar national traditions. It was apparent to Pater's earliest readers that he was not practicing history writing equally they had come to expect it, based in known facts and organized around a distinct time and place. Pater's friend Emilia Pattison (the art critic later known as Emilia Dilke) writes in her review that the book's title is "misleading; the historical element is precisely that which is wanting, and its absence marks the weak place of the whole book . . . . the work is in no wise a contribution to the history of the Renaissance" (Westminster Review, April 1873; qtd. in Seiler 71).[4] Pater's subjective method, applying his own unusual sensibilities to artworks of the by, must inevitably be ahistorical. Equally Margaret Oliphant notes, Pater imparts sentiments that "never entered into the about advanced imagination within 2 or three hundred years of Botticelli's time, and [were] as alien to the spirit of a medieval Italian, as [they are] perfectly consequent with that of a delicate Oxford don in the latter half of the nineteenth century" (Blackwood's Magazine, Nov. 1873; qtd. in Seiler 88). Pater responded to these criticisms past retitling the book in afterward editions as The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry.

Pater'southward challenge to the scholarly practice of history takes place on multiple levels. Carolyn Williams has shown that his "aesthetic historicism" is grounded in a radical skepticism toward the idea of history itself, asserting the impossibility of whatever kind of historical recovery, return, or revival (5).[5] That skepticism is also evident, I would add, in the bold untruths Pater presents using the deadpan tone of the scrupulous scholar. Indeed, The Renaissance is riddled with inaccuracies—deliberate misattributions of paintings, citing of legends known to exist fake, misquotations from authorities, inexact or spurious translations, stories retold or changed for romantic effect; as Sidney Colvin warns in his 1873 review, "The volume is not 1 for whatsoever beginner to turn to in search of 'information'" (qtd. in Seiler 50). The numerous mistakes and modifications of Pater'south Renaissance are thoroughly documented in Donald Fifty. Hill's 1980 annotated edition. Adam Phillips observes that Pater footnotes the word "kissing" in the Winckelmann essay with the note "Hermann, Th.ii.c.two.s21, (north.)sixteen" in the book's first two editions, hinting at a parody of scholarly apparatus. Phillips draws the cautious conclusion that Pater's factual errors are perhaps "idiosyncratic rather than unscrupulous" (9), merely we might conclude more forcefully that Pater deliberately ironizes the conventions of mod history-writing in order to enact the values he finds in the Renaissance, every bit different artists and critics over time overthrow the constraining limitations of their eras. In Pater's own moment, humanities scholarship was being constrained by the fact-based methods of scientific reason, whose denuding and sterile approach (from a Paterian perspective) opposed the more febrile, ecstatic, and irrational forces of passion and lived feel. When Pater quotes Matthew Arnold in simulated agreement and so moves direct to contradict him, this oblique ironic reversal encapsulates one of The Renaissance's major destructive tactics, aimed at the hierarchies of cultural establishment and fifty-fifty at the accustomed structures of knowledge themselves.

Returning to Pater's footnote of the word "kissing": non coincidentally, this moment occurs in his essay on the High german classical scholar J. J. Winckelmann, by far the longest essay in the collection besides equally the most manifestly homoerotic. Winckelmann is non himself an artist merely an fine art historian, and hence serves as a model for the Paterian type of the mod critic. Winckelmann's methods are certainly unusual—he makes a fake conversion to Catholicism to gain admission to Rome, and he cultivates "romantic, fervent friendships with young men" in the spiritual-sexual pursuit of the erotic male bodies depicted by Greek sculpture (Pater 93-94). (See, for instance, Fig. iv.) His practice of fine art history is non intellectual merely enthusiastic and sensuous; he understands Greek art "past instinct or touch" (95). Winckelmann's art-critical scholarship encompasses frank sexual pleasure every bit a fashion to "know" the human form, a pun that describes a noesis of and through the body: "He has known, he says, many young men more than beautiful than Guido'southward archangel" (94). The singled-out homoeroticism of this essay makes it hitting that few of the book'southward 1873 reviewers noted anything unusual almost the piece; Sidney Colvin calls information technology "completely excellent from starting time to end" (qtd. in Seiler 52). Again, Pater'south moderate, scholarly tone lends a veneer of respectability to a potentially scandalous theory of art criticism.

Figure 4: Cavalcade, Block II from the west frieze of the Parthenon, ca. 447–433 BC

Pater's appropriation of the classical scholar Winckelmann for Renaissance history locates his volume within the homosocial tradition of Greek Studies at Oxford—producing what Linda Dowling has influentially termed a "homosexual code" by which writers like Pater and Wilde could quietly invoke a "homosexual counterdiscourse able to justify male love in ideal or transcendental terms" (xiii). For Victorian readers in the know, Greek civilization might exist used to signal secret sexual preferences. All the same information technology is worth pointing out that Pater's Hellenism in the Winckelmann essay goes beyond mere code signaling. This essay is distinctive, like all of Pater's writing, for its investment in punning and wordplay, a lawmaking inside a code. Using linguistic cunning, Pater still once more ironizes his rational, scholarly disguise. For example, a verbal joke recurs in the way both Goethe and Winckelmann are said to "handle the antique," engaging with classical art in a quasi-physical manner that accentuates the hands (87, 88). Winckelmann "fingers those pagan marbles with unsinged easily, with no sense of shame or loss. That is to deal with the sensuous side of art in the pagan mode" (112). In Pater's telling, Winckelmann'south sexualized appreciation of male sculpted bodies is not shameful because heathen civilisation itself glorified the male body in a normative mode. (This ideal stands in stark contrast to Christianity, described in the essay as "the grit of Protestantism" [91] with its "crushing of the sensuous" [113] and "mankind-outstripping interest" [113], and implicitly encompassing the Victorian Christianity of Pater's own day.) "Treatment" is a key term for Pater across all of The Renaissance's essays, invoking both an artist's bright execution of form and the critic's sensuous reception of the creative person'southward piece of work. The erotic overtones of this word echo slyly beyond Pater'southward volume. Obliquity itself is both a strategy and a philosophical ideal for him, equally the erotic tremors and insinuations of language cause words to manifest themselves every bit a beautiful screen.

The near influential pages of The Renaissance come in its cursory "Conclusion." Only three pages long, this artful manifesto—adapted from Pater's 1868 review of William Morris's Earthly Paradise—turns away from the explicit subject of Renaissance art to address the reader directly. What matters well-nigh in life, according to Pater? Not any of the usual Victorian middle-class values of Christian faith, moral rectitude, social condition, business competition, fiscal gain, nor any kind of public life. Facing the stark fact of man mortality, Pater exhorts his readers to take pleasure in sense impressions and in the pursuit of cognition, whether admiring an artwork or some other person:

A counted number of pulses only is given to us of a variegated, dramatic life. How may we see in them all that is to be seen in them by the finest senses? How shall we pass most swiftly from point to signal, and be present always at the focus where the greatest number of vital forces unite in their purest energy?

To burn e'er with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life. In a sense it might even exist said that our failure is to form habits: for, after all, habit is relative to a stereotyped world, and meantime it is only the roughness of the centre that makes whatsoever ii persons, things, situations, seem alike. While all melts under our feet, we may well catch at any exquisite passion, or any contribution to cognition that seems by a lifted horizon to set the spirit free for a moment, or any stirring of the senses, foreign dyes, strange colours, and curious odours, or piece of work of the artist's hands, or the face of one'due south friend. (119-20)

The idea of the Renaissance here takes on its broadest possible pregnant, alluding to a cultural rebirth possible for Victorian readers as much as Italian painters. In a Victorian world defined past strict etiquette and astringent conventionality, we can sympathize why Pater'due south recommendation of "ecstasy" as the best life path invited immediate controversy.

2. Reception

In the legend surrounding The Renaissance, Pater'southward book exploded onto the Victorian cultural scene in 1873 and, with its bold embrace of atheism and hedonism, plunged him into a scandal from which his career never recovered. While this legend contains elements of truth, the actuality seems to accept been more complex. In the first instance, The Renaissance drew disapproval within the hothouse world of Oxford, where Pater spent his academic career. Negative responses came especially from Oxford'southward religious and conservative quarters.[vi] John Wordsworth, one of Pater'southward former students and Chaplain of Brasenose Higher, wrote an oftentimes-quoted letter to Pater in 1873 describing his pained thwarting in the book:

I cannot disguise from myself that the concluding pages adequately sum upward the philosophy of the whole; and that that philosophy is an assertion, that no fixed principles either of faith or morality can be regarded equally certain, that the merely thing worth living for is momentary enjoyment and that probably or certainly the soul dissolves at decease into elements which are destined never to reunite. (qtd. in Seiler 62)

Mary Augusta Ward, twenty-three at the time of The Renaissance's publication and living in Oxford, recalls in her 1918 memoir

the outcome of that book, and of the strange and poignant sense of beauty expressed in it; of its entire aloofness also from the Christian tradition of Oxford, its glorification of the college and intenser forms of esthetic pleasure, of "passion" in the intellectual sense—as against the Christian doctrine of self-denial and renunciation. It was a doctrine that both stirred and scandalised Oxford. The bishop of the diocese thought information technology worthwhile to protest. There was a weep of neo-paganism, and diverse attempts at persecution. (A Author'due south Recollections, 1918; qtd. in Seiler nineteen).

Particularly within the world of the university, Pater's book was seen by critics as a dangerous and alluring influence on young men. When the Bishop of Oxford preached a sermon against The Renaissance in 1875, he complained that "too many of the younger students go miserably off-target" under the dissentious guidance of atheistic mentors. Quoting from Pater's "Conclusion," the Bishop asks, "Can you wonder that to young men who take imbibed this education the Cross is an offence, and the notion of a vocation to preach it an unintelligible craze?" (qtd. in Seiler 96).

As these comments would advise, "young men" were a specially worrying and vulnerable demographic in late-Victorian Oxford, prone to all kinds of hazardous enticements. Feet about immature men seems to have been exacerbated at Oxford in the late 1860s and 1870s, during what Linda Dowling has described as an "interval of particularly intense male homosociality"—before university reforms eliminated the celibacy requirement for fellows in 1884, and earlier Oxford's first residential colleges for women were founded in 1879. Dowling suggests that this menstruation at Oxford was a "halcyon" moment for homosociality based in "the ethos of a wholly male residential society" (85), only the Oxford response to Pater'due south Renaissance suggests that anxieties as well abounded, particularly in the close relationships between dons and students fostered by the tutorial arrangement. A. C. Benson unwittingly captures the aureola of business organization surrounding vulnerable young men in an early biography of Pater, presenting a all the same quite Victorian worldview in 1906: "Young men with vehement impulses, with no feel of the world, no idea of the solid and impenetrable weight of social traditions and prejudices, found in the principles enunciated by Pater with so much recondite beauty, so much magical charm, a new equation of values" (52). Rhetoric surrounding the suggestible young man ironically worked to eroticize and sensationalize the very subject it attempted to protect. We find hints of this rhetoric in the well-known footnote Pater appended to the third edition of The Renaissance (1888), in which he explains his decision to omit the "Determination" from the second edition (1877):

This brief "Conclusion" was omitted in the 2nd edition of this volume, every bit I conceived it might possibly mislead some of those young men into whose hands it might autumn. On the whole, I have thought it all-time to reprint it here, with some slight changes which bring it closer to my original meaning. I accept dealt more than fully in Marius the Epicurean with the thoughts suggested in it. (qtd. in Pater, Renaissance, ed. Beaumont 177)

Many scholars, including A. C. Benson, have taken Pater'south cautious actions after 1873 as the sign of his life-long retrenchment from the controversial positions staked out in The Renaissance. Yet it is ultimately difficult to take Pater's footnote at face value. Judging from the contents of The Renaissance, 1 might conclude that misleading young men was, in fact, a desirable activity. The footnote directs us over again to young men'due south "hands," presenting the transfer of knowledge as an erotic passage from book to receiver—one that might indeed lead to a "fall," with all the forbidden and sexualized connotations of the word. Such a moment of impressionable reading is captured in Pater'due south novel Marius the Gluttonous (1885), as the adolescent Marius discovers the "gilded book" (67) of Apuleius's Metamorphoses in an human activity of "truant reading" (66) that stirs his character and stays with him for life. While Pater'south footnote ostensibly follows the Bishop of Oxford in showing business for the well-being of young men, his linguistic communication also hints at an ironic and subversive relationship to that responsible administration.

After the 1873 publication of The Renaissance, Pater failed to succeed in Oxford competitions for academic promotion. In 1874, a promised proctorship was withheld at the concluding moment by Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol College and Pater's former mentor. Letters found belatedly in the twentieth century advise that Jowett's decision was the immediate result of an uncovered epistolary "romance" between Pater and a nineteen-year-quondam undergraduate, William Coin Hardinge, known for his open homosexuality.[7] In 1877, Pater was forced to withdraw his awarding for the professorship of poetry at Oxford because of veiled homophobic attacks on his candidacy, likely inflamed by the devastating satire of W. H. Mallock's The New Republic, which had been circulating in serial form since June 1876 (Dowling 112). Mallock depicts Pater every bit the thinly disguised "Mr. Rose," an aesthete whose effusions about beauty are tinged with sexual allusion. "What a very odd human Mr. Rose is!" one grapheme exclaims, "He always seems to talk of everybody as if they had no dress on" (Mallock 350).

Outside the earth of Oxford, nonetheless, the reception of The Renaissance was actually quite favorable. Many of the reviews were positive, and some of them outright admiring. Though almost of the volume had previously appeared anonymously in essay form beginning in the tardily 1860s, the book's publication drew full-bodied attending from critics every bit it circulated among the periodical-reviewing crowd.[8] John Morley praised the emergence of "a learned, vigorous, and original school of criticism" that made a desirable "English contribution to the inquiry and idea of Europe" (The Fortnightly Review, April 1873; qtd. in Hill 287). Almost all of the reviews, even those hostile to the volume, expressed esteem for Pater's jeweled prose mode. R. H. Hutton commented in The Spectator that the book's best passages, though "perhaps too visibly laboured, have subtle touches of lovely color, and a sweet, tranquillity cadence, hardly amounting to rhythm, which are distinguishable from those of poetry but in form" (June 1873; qtd. in Colina 287). (W. B. Yeats continued the tradition of reading Pater poetically when he chose the notorious Mona Lisa passage as the opening poem for his 1936 Oxford Book of Modern Verse, breaking up Pater'south paragraphs into free verse.) While our contemporary view has tended to emphasize The Renaissance as a publishing scandal, many readers and reviewers embraced Pater'due south artful scholarship. It does remain an open question, though, to what extent Victorian readers understood the ironic or insinuating quality of much of the book's writing.[9]

If The Renaissance can be claimed as the major theoretical work of the Aesthetic motion, it remains to be discussed to what extent the book was linked to the broader popularization of the motility in the later on 1870s and early 1880s. A direct link is not obvious; Walter Hamilton's 1882 report The Aesthetic Motility in England does non mention Pater. However The Renaissance was a central inspiration for followers such as Oscar Wilde, who preached the cult of dazzler to a wide audience in both United kingdom and America. (Wilde called The Renaissance his "gilt book," and claimed to travel with it everywhere [Seiler 2].) Ideas that first circulated amid an aristocracy, artistic circle in the late 1860s began to diffuse to a larger middle-class crowd, leading to the creation of a recognizably "aesthetic" lifestyle.

The Renaissance offered a theory of living centered around the experience of art and beauty; just what would it mean to put these philosophical ideals into exercise? Satirists were quick to attack the pretensions of aesthetes, whose values seemed ineffectual and absurd when performed in the real world. George Du Maurier published a series of ingenious cartoons mocking aesthetes in the sense of humour magazine Punch, each one playing on the incongruity between an aesthete's highflown ideals and the giddy beliefs by which he expressed them. In "An Aesthetic Mid-Day Repast" (1880), an aesthete in a restaurant contemplates a lily with dreamy absorption, rejecting the solicitations of a puzzled waiter. Instead of nourishing his body with food, the aesthete needs merely the beauty of the lily—suggesting an unnatural relationship to the torso, equally visual pleasure replaces the more usual gustatory experience. The aesthete besides stands out for his effeminate masculinity, credible in his languid and unmanly posture. The signature pose of aestheticism was passive, dreamy, and reclining, a pose performed in resistance to the mainstream masculinist values of progress, work, and arduous labor. Pater'southward Renaissance made male passivity into a virtue, as receptive artists and spectators opened themselves to the flood of the world's impressions. This not-normative masculinity was reflected in the new popular identity of the aesthete, whose sexual dissidence functioned as part of a broader rebellion confronting middle-grade cultural norms.

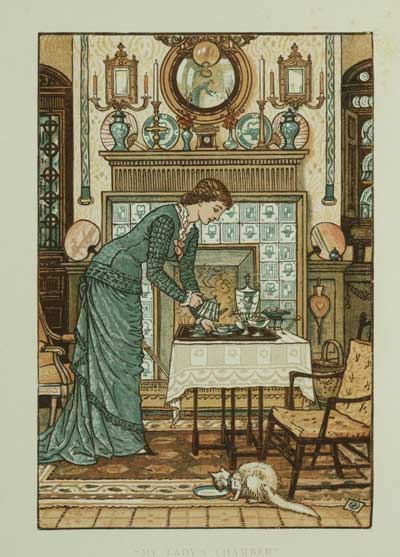

Figure 5: Walter Crane, "My Lady'southward Bedroom," frontispiece to _The Business firm Beautiful_ (1878), reproduced with permission of the Pennsylvania State University Libraries

If The Renaissance presents Winckelmann every bit a new ideal type of manhood, that type too entails a passionate delivery to art and an artistic lifestyle. Translated into the Victorian earth, that commitment was expressed by aesthetes participating in a vogue for artistic home décor.[ten] A typical artful home is depicted in the frontispiece to Clarence Cook's The House Beautiful (1878), rendered by illustrator Walter Crane, with prc plates, fancy tea ware, patterned rugs and wallpapers, and Japanese fans. (See Fig. 5.) George Du Maurier ridicules both male person and female aesthetes with his cartoon "The Half-dozen-Mark Tea-Pot" (1880), in which an "Intense Bride" clutches a teapot and declares to her "Aesthetic Bridegroom," "Oh, Algernon, let us alive upwardly to it!" Rather than devote themselves to more than typical newlywed behaviors, these two aesthetes take channeled their nuptial energies into their home décor. Du Maurier captures the embarrassing distance between Pater'due south elevated theory of dazzler and the more mundane practice of artful collectors, who made decorative items like teapots into sacred objects of worship.

Du Maurier's teapot drawing points the states to a perhaps surprising fact most popular aestheticism, given what nosotros might have expected from Pater's volume: namely, that the movement engaged women as well as men. For all of Oxford's focus on endangered "young men," in fact women as well embraced aestheticism as role of a broader sexual clinker. Pater'southward Renaissance largely focuses its erotic energies on men—male artists pursuing male lovers and the perfection of a universalized yet distinctly male "homo form." The volume's female person figures appear mostly as subjects within artworks, such equally the Mona Lisa, and their rendering is so odd and idiosyncratic as to empty them out as human agents, making them appear every bit purely symbolic or poetic figures.[eleven] Yet, despite the male person-centered focus of Pater's book and of the cloistered aesthetic preserve of Oxford, some Victorian women saw in aestheticism the hope of an escape from restrictive gender roles and binding social conventions. Talia Schaffer has located many of the "forgotten female person aesthetes," late-Victorian women writers who affiliated themselves with the movement such as Ouida and Rosamund Marriott Watson.[12] Yopie Prins, in "Greek Maenads, Victorian Spinsters," describes how a generation of female classical scholars subsequently Pater followed his example past using the alternative gender behaviors of antiquity to legitimate their own queer pathways. Women also supported the aesthetic lifestyle every bit patrons of the arts, collectors of aesthetic objects, even as wearers of dresses freed from corsets. Though Pater'southward Renaissance may seem to be aimed in the beginning instance at a small and elite group of male readers, the book's bulletin of liberation—when "the imagination feels itself free" (88-89)—offered an idea of aesthetic, erotic, and intellectual liberty to any potential viewer with the right kind of creative instruction.

published September 2012

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Teukolsky, Rachel. "Walter Pater's Renaissance (1873) and the British Aesthetic Movement." Co-operative: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last appointment of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Benson, A. C. Walter Pater. London: Macmillan, 1911. Impress.

Dellamora, Richard. Masculine Desire: The Sexual Politics of British Aestheticism. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1990. Impress.

Donoghue, Denis. Walter Pater: Lover of Strange Souls. New York: Knopf, 1995. Print.

Dowling, Linda. Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford. Ithaca: Cornell Up, 1994. Impress.

Du Maurier, George. "An Artful Mid-Day Meal." Dial 79 (17 July 1880): 23. Print.

—. "The Six-Mark Tea-Pot." Dial 79 (30 Oct. 1880): 194. Print.

Fraser, Hilary. The Victorians and Renaissance Italia. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. Print.

Hamilton, Walter. The Aesthetic Movement in England. London: Reeves & Turner, 1882. Impress.

Hauser, Arnold. The Social History of Fine art. 1951. Vol. ii of Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque. four vols. Taylor & Francis E-Library. Taylor & Francis, 2005. Spider web. 25 May 2012.

Hinojosa, Lynne Walhout. The Renaissance, English Cultural Nationalism, and Modernism, 1860-1920. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. Impress.

Inman, Billie Andrew. "Estrangement and Connection: Walter Pater, Benjamin Jowett, and William G. Hardinge." Pater in the 1990s. Ed. Laurel Brake and Ian Modest. Greensboro, NC: ELT, 1991. 1-20. Print.

Mallock, Westward. H. The New Democracy; or, Culture, Religion, and Philosophy in an English Land Firm. Bk. 3—Ch. 1. Belgravia: A London Magazine thirty (Jul.-Oct. 1876): 343-threescore. Hathi Trust Digital Library. Web. 25 May 2012.

Levey, Michael. The Case of Walter Pater. London: Thames & Hudson, 1978. Print.

Levi, Donata. "'Permit Agents be Sent to All the Cities of Italy': British Public Museums and the Italian Fine art Market in the Mid-Nineteenth Century." Victorian and Edwardian Responses to the Italian Renaissance. Ed. John E. Law and Lene Ǿstermark-Johansen. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2005. 33-53. Print.

Pater, Walter. Marius the Gluttonous. Ed. Michael Levey. New York: Penguin, 1985. Print.

—. The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. The 1893 Text. Ed. Donald Fifty. Hill. Berkeley: U of California P, 1980. Impress.

—. Studies in the History of the Renaissance. 1873. Ed. Matthew Beaumont. Oxford: Oxford Upward, 2010. Print.

Phillips, Adam. Introduction. The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. By Walter Pater. Ed. Adam Phillips. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1998. vii-vxiii. Print.

Prins, Yopie. "Greek Maenads, Victorian Spinsters." Victorian Sexual Clinker. Ed. Richard Dellamora. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999. 43-81. Print.

Schaffer, Talia. The Forgotten Female Aesthetes: Literary Culture in Late-Victorian England. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 2000. Print.

—, and Kathy Psomiades, eds. Women and British Aestheticism. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 1999. Print.

Seiler, R. Grand. Walter Pater: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980. Print.

Teukolsky, Rachel. The Literate Eye: Victorian Art Writing and Modernist Aesthetics. New York: Oxford Upward, 2009. Print.

—. "The Politics of Formalist Art Criticism: Pater's 'School of Giorgione.'" Walter Pater: Transparencies of Desire. Ed. Laurel Restriction, Lesley Higgins, and Carolyn Williams. Greensboro, NC: ELT, 2002. 151-69. Impress.

Wallen, Jeffrey. "Alive in the Grave: Walter Pater's Renaissance." ELH 66.4 (Winter 1999): 1033-51. JSTOR. Spider web. 12 May 2012.

Williams, Carolyn. Transfigured Earth: Walter Pater's Aesthetic Historicism. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1989. Print.

Yeats, W. B., ed. The Oxford Volume of Modern Verse, 1892-1935. Oxford: Clarendon, 1936. Print.

ENDNOTES

[one] See Levi; Fraser 63-66.

[ii] See Teukolsky, "Politics" 157; also Hinojosa.

[three] All quotations are taken from the 2010 Oxford Studies in the History of the Renaissance, edited by Matthew Beaumont, which reproduces the 1873 start edition of Pater'due south book. 3 later editions of the book appeared in Pater's lifetime, each with many small and incremental changes of wording. Hill's 1980 annotated edition, which uses the 1893 Renaissance as its copy-text, documents all of the textual variants across the book's dissimilar editions.

[iv] Emilia Dilke (1840-1904), born Emily Francis Strong, became "Mrs. Marker Pattison" afterward her commencement union in 1861, and later "Lady Dilke" or "Emilia Dilke" later on her second wedlock in 1884. She was a prolific art critic and reviewer as well as a noted art historian specializing in French art. Come across her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for a more in-depth account.

[5] Williams' book Transfigured Earth is an of import study of Pater's "aesthetic historicism" that can only be touched on briefly here. It serves as 1 of the major in-depth analyses of Pater'due south complex philosophical engagements.

[half dozen] Encounter Levey 142-44; Donoghue 55-64; Dowling 100-03.

[7] Encounter Inman.

[8] The essay on Winckelmann (1867) appeared in the Westminster Review, equally did "Poems by William Morris" (1868), from which the "Conclusion" to The Renaissance was fatigued. The Fortnightly Review published the essays on Leonardo da Vinci (1869), Sandro Botticelli (1870), and Michelangelo (1871). An essay on "The School of Giorgione," appearing in the Fortnightly Review in 1877, was added to the tertiary edition of The Renaissance in 1888. Because of this later publication date of "The Schoolhouse of Giorgione," I do not hash out the influential essay here; my focus is on the 1873 first edition of The Renaissance.

[9] The same question might be asked of more mod readers. Rupert Crofte-Cooke writes in his 1967 archetype Feasting with Panthers: "The words in [Pater's books] are manipulated with a cunning virtually unprecedented in English prose, merely they have no guts. If Pater had anything to say he never dared to say it" (qtd. in Seiler 3). Crofte-Cooke's analysis does not allow for the thought that Pater cultivated obliquity or indirection as essential aspects of his aesthetic and erotic philosophy.

[10] Encounter Teukolsky, Literate Middle 127-36.

[11] Scholars such as Richard Dellamora have even argued that The Renaissance's famous female characters are "phallic women," or masculinized self-portraits of the artists (meet 136-46). Normative Victorian femininity is difficult to locate inside these essays.

[12] See likewise Schaffer and Psomiades.

Source: https://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=rachel-teukolsky-walter-paters-renaissance-1873-and-the-british-aesthetic-movement

0 Response to "Italian Renaissance Art Volume One Second Edition Vol 1 Second Edition"

Post a Comment